Japan Report - Kabuki at the Kabukiza Theater

On Monday, April 10th, I went to the Kabukiza Theater in Tokyo to see the April Performances. Three pieces were part of the morning matinee:

醍醐の花見 - Flower Viewing at Daigo Temple - Toyotomi Hideyoshi stages a lavish party to view the sakura, or cherry trees, blooming at Daigo Temple.

伊勢音頭恋寝刃 - A Summer Play of Love’s Dull Blade - The effort of a loyal retainer to retrieve a cursed sword and its certificate of authenticity from the samurai that swindled it from his master.

一谷嫩軍記 - War Chronicle of the Battle of Ichinotani Valley - Two women on opposite sides of a war go to the battle camp of the general leading one side to see if their sons survived.

This was my first time viewing live kabuki performances or seeing an entire performance cycle. I had learned some things about kabuki over the years, but wasn’t sure quite what to expect.

Here’s a bit of what I found out…

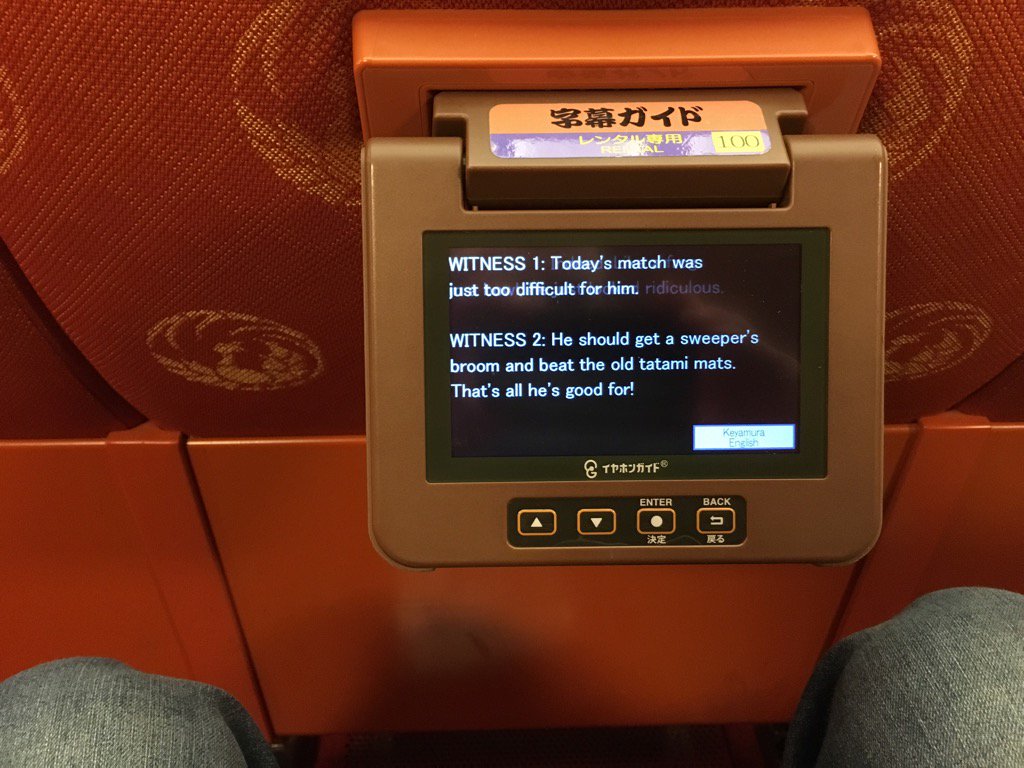

First, expect to be confused. First, it’s in foreign language. And a version of that foreign language that is foreign to the people that speak it. Japanese can and do rent earphones that will give them explanations of what is being said during the performance. And foreigners can rent small screens that translate the lines of the play into English or other languages, providing you with subtitles during the performances.

But that only helps to a certain degree. The subtitle box you rent tells you that the subtitle it provides is based on the original text of the play, which might be different from what actor is actually saying on stage. There were moments when even I could tell that the line the actor was saying was different than what was on the screen.

But the confusion doesn’t end there. Adding to it is the fact that, from what I could tell from the performances I saw, a number of these presentations are fragments of older, longer pieces. Of the three pieces I watched as part of the performance I attended, one was the favorite third act of a five act play and another has segments that are “not often performed” for modern audiences. The previous parts of these longer pieces have characters and exposition that would help make it clear as to what you are watching before you if you had no familiarity with the piece. It would be like someone from another country that never heard of Romeo & Juliet going to performance that started with the balcony scene.

And even with the one stand alone piece in the performance, a “dance program” entitled “Flower Viewing at Daigo,” there is a historical context that a foreign viewer may lack. This piece is based on an actual historical event when Totoyomi Hideyoshi, then overlord of Japan, staged a lavish party to view the blooming sakura, or cherry blossoms, at Daigo Temple near Osaka. What someone not familiar with Japanese history wouldn’t know is that this flower viewing party took place only a few months before Hideyoshi’s invasion of Korea ended in disaster, followed by the collapse of his power and subsequent death. Sakura is the Japanese symbol of the ephemeral nature of life. There is an irony to the piece, not lost on the Japanese, in Hideyoshi celebrating his power and prestige with a party that would be linked with fragility and fleeting nature of life.

As with my example using Romeo & Juliet above, these plays are well known to the Japanese people that come watch them. They have the same thrill of recognition as when an English speaking audience hears Juliet asks, “Wherefore art thou Romeo?” The audience will applaud, and laugh, at this famous moments. The performers themselves will pause and present a tableau when these scenes arrive in the performance.

Which is another aspect of kabuki that stands out to someone steeped in western theatre arts: they are very, VERY stylized and presentational. The artifice is part of the performance, not just the vehicle by which the performance is conveyed to the audience. This is most clear when it comes to fight scenes. They are not staged to look like actual combat. They are dances of violence. At times they can almost taken to be walk throughs by stunt people before the actual scene is staged. A red scarf, pulled out from the neckline of an actor’s kimono is an indication that the fight has come to an end.

This is not to say I didn’t enjoy the performance. I did. As with any works of art carried forward from the past into the present day, there is something about them that we, or the culture that produced them, finds valuable and meaningful, which has lasted in the decades or centuries when they were first created.

The scene I remember most clearly that conveys this comes from the third piece in the performance I attended, entitled, “War Chronicle of the Battle in Ichinotani Valley.” A mother, wife to the general leading the forces in one side of the battle, defies orders and comes to the camp to see if her son has survived. Her husband, angry at her disobedience, questions her about her duty as a mother and their son’s as a soldier.

“If I told you that our son fought bravely, and died doing his duty honorably, what would you say to that?”

“Yes,” she replies, she would be happy to know that was how their son behaved at the end of his life. But off to the side, the narrator, with musical accompaniment, recites the woman’s thoughts and feelings that she keeps inside her. And as she speaks out loud the dutiful answers expected of her, you can hear her voice echo the timbre and trembling of the narrator, and you can feel how much she hurts over the idea of discovering her child has met his end.

There is emotional truth in this plays. That is why they are still performed after so many years have past.

The experience itself was a very Japanese one, for sure. From the entire staff spoke nothing but keigo, the most polite level of Japanese, to the bento box I bought for the lunch break, it was an experience steeped in Japanese sensibilities.

I don’t know that I’ll become a kabuki fan. But I do see myself going again, to see what else I might find there. I don’t think I have to worry about kabuki going away any time soon.